This note is a companion piece to Generative AI is a Resurrection Machine.

Download a PDF copy of Remembering the Face of Your Father (paid subscribers only).

Five years ago, I wrote a series of notes called The Long Now.

Those notes covered a lot of ground, and in particular introduced the core Epsilon Theory idea of Make / Protect / Teach, but the Narrative heart of those notes was this story about my father.

It was the summer of 1996, early June, and I was teaching a course at Simmons College in Boston to make some extra dough. Jennifer was clerking for a lawfirm down in Dallas, pregnant with our first child. My dad called. He and my mom were in London, where they had rented a small flat for a month. Did I want to come over and stay for a few days? As it happened, I had five days free, perfect for a long weekend trip. I walked down to a cheapo travel agency on Boylston (yes, a physical travel agency), and found a ticket for $600 or thereabouts. Seemed like a lot. I could have afforded it, by which I mean there was room on my credit card to buy it, not that I could really afford it. $600 was a lot of money to me. That said, I hadn’t seen my parents since Christmas, and my dad sounded so … happy. This was a special trip for them, a chance to LIVE in a city that my father LOVED, and this was my chance to share it with them. But $600. I dunno. I called my father and told him that I just couldn’t swing it. He understood. He was a very practical guy. The call lasted all of 20 seconds. You know, international long distance being so expensive and all.

I never saw my father again. He died a few weeks after he and my mother got home.

Tick-tock.

Yeah, I know a few things about Time.

I know that the moving finger writes, and having writ, moves on.

I know that I would give anything to go back to that week in June 1996 and buy that stupid ticket that I couldn’t “afford” but really I could afford and spend five more days with my father and not do anything special but just BE with him and share a beer at that pub that he mentioned on the phone but that I just can’t remember the name of no matter how hard I try and it’s weird but that’s what bugs me most of all.

Tick-tock.

It’s not an exaggeration that I’ve spent the past 28 years trying to figure this out.

Not so much the name of that London pub (although yes, that too), but how to stop the tick-tock that’s been in my head ever since.

Not so much the tick-tock of straight up mortality (although yes, that too), but the tick-tock of a finite amount of time to tell my story, to say what I want to say to MY children, to not be cut off mid-conversation, decades too soon, like I was with my father.

Not so much because I’ve got something oh-so special to say (although yes, that too), but just to BE there for my children and my children’s children, to hear their stories and to share my stories, to transmit to them through the telling of my stories a grounding and an experience and a love and a secure knowledge that you are not alone, that you are never alone.

I can tell my father’s stories to my children, and they listen and it’s all good. But he died before any of them were born. They have no stories about my father from their own experience with him, and when I am gone there will be no one left to tell my father’s stories. When my children are gone there will be no one left who has ever heard my father’s stories, much less someone to tell them anew. And that’s when my father will truly die. The true death – the final death – is the death of your stories.

Tick-tock.

In modern Western culture it typically takes three generations for your stories to die, before there’s no one left on Earth who has ever heard them. Once you get to great-grandchildren, that’s about it.

It wasn’t always this way. Most pre-modern societies, whether you’re talking about the Americas, Asia, Africa or Europe, saw communion with their ancestors — a holy celebration that included direct communication with the dead, even the long-dead — as a foundational pillar of civilization.

For example, every year, ancient Romans spent the better part of February communing with their dead, including a nine-day festival called the Parentalia where everything from temples to shops to government offices were shut down so that families could share the stories of their ancestors, not in a dry, distant, recital sense but in a celebratory, vibrant, participatory sense. And when I say participatory I don’t just mean the participation of the living but also the participation of the dead. To the Romans, the spirits of the dead (manes) stayed among the living, along with all the other spirits of things and ideas and places and people (lares and penates). There was little distinction between the spirit world and the physical world, or rather spirits co-existed in multiple worlds at once and could be focused in and through physical objects, and communication — story telling! — was absolutely possible across worlds. Remember the scene in Gladiator where Maximus is holding the figurines of his dead wife and son and talking with Juba about his conversations with them? That’s what religion WAS in so many human cultures, not just ancient Rome but ancient China and ancient India and ancient Egypt and pretty much ancient everywhere, the ability to commune with the dead and receive comfort and wisdom from those conversations.

What stopped this bedrock human practice of speaking to your ancestors through ceremony and religion?

First, the Abrahamic religions — Judaism, Christianity and Islam — have always had a fairly adversarial relationship with ancestral communion. Josiah, King of Judah some 600 years before Christ, abolished all ceremonies associated with ancestor remembrance as they veered too closely towards Egyptian ‘necromancy’. Today, Catholicism and the Eastern Orthodox Church encourage a one-way conversation with the holy dead in the form of the veneration of saints, as they are ‘intercessors’ with God, but do not formally allow communication with the ordinary dead for the same reasons as Josiah. Protestantism, with its emphasis on a direct relationship between humans and God, discourages even the veneration of saints, as their intercession with God is unnecessary if not unwelcome. There’s a similar split in Islam, where the veneration of saints is allowed in some practices, particularly Sufism, but where Wahhabism rejects even this (and has destroyed many sacred Islamic sites associated with Sufi saints as a result). In almost every Judeo-Christian and Islamic tradition, the idea of communicating directly with the dead is blasphemy. There are a few exceptions — the Mexican Day of the Dead, for example — but all of these exceptions are pure Syncretism, where (very) old pagan religious ceremonies have been absorbed into the local expression of Christianity or Islam. For the overwhelming part, if you believe in the God of Abraham you can pray for the dead, and in some traditions you can ask the holy dead to intercede with God on your behalf, but you can’t talk with the dead. You can’t hear their personal stories and you can’t receive their personal counsel through the ceremonies and teachings of your religion.

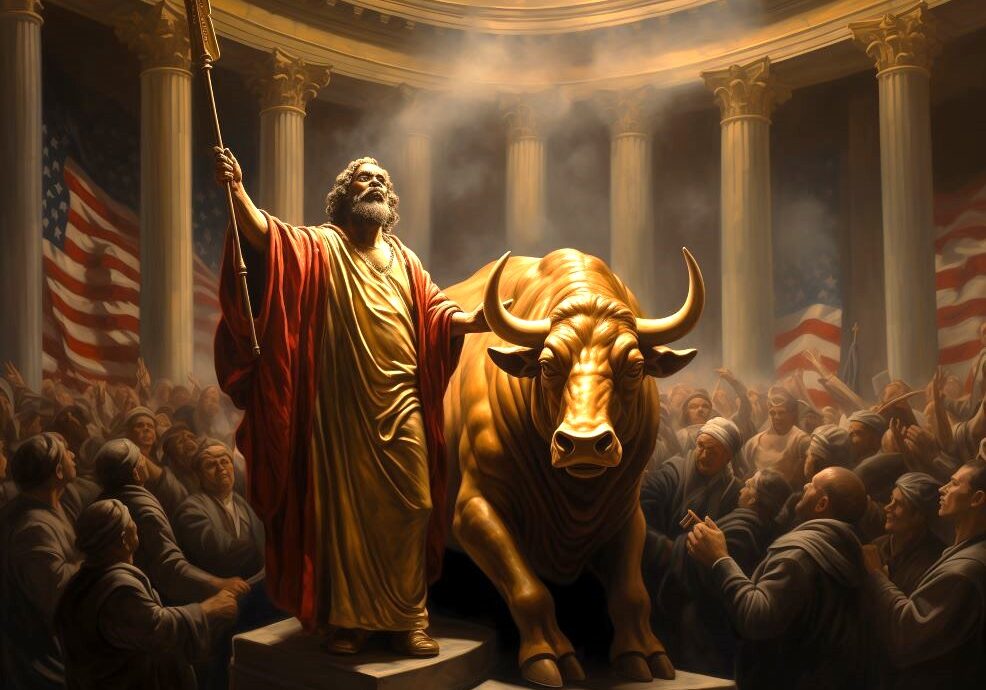

Second, modernity — in its worship of Science, its worship of the State, and its worship of Capital — is enormously hostile to any form of ancestral veneration, much less communion. The dead are dead. There’s no heaven, no spirit world, no consciousness or entity that can be spoken with after death even if you wanted to. It’s lights out for the dead and time to ‘move on with your life’ for the living. We live in a materialist world of a constant and never ending present, what I call The Long Now, where all of human motivation is reduced to ‘incentives’. Marx got it right when he focused on the enormous power of modern society to alienate us, in the true and awful sense of the word meaning ‘separation’, but he got it wrong in saying that this alienation was fundamentally a separation from our work. Yes, our work is a crucial part of our identity and what makes us human, and yes, the abstraction of our jobs from our work is a society-melting acid of the worst kind (see In Praise of Work). But even more crucial and even more subject to the alienating and separating power of modernity is our family. Our families — particularly our extended families of those who came before us — are blasted to smithereens by modernity. We are cheerfully led into an embrace of the Hive, where we are not loved but used, and where the individual and individualistic stories of our parents and grandparents and great-grandparents are replaced by the collective and collectivist stories of the Nudging State and the Nudging Oligarchy.

Stephen King, of all people, captured all this so well in The Dark Tower series, which is not just a fantasy retelling of Camelot through the mythos of the American West and the American present (although yes, that too), but a presentation of what is lost as a society when we lose the stories of those who came before us … at scale.

“Have you forgotten the face of your father?”

That’s the line and the words that weave throughout Stephen King’s magnum opus.

I do not aim with my hand; he who aims with his hand has forgotten the face of his father.

I aim with my eye.

I do not shoot with my hand; he who shoots with his hand has forgotten the face of his father.

I shoot with my mind.

I do not kill with my gun; he who kills with his gun has forgotten the face of his father.

I kill with my heart.

In The Dark Tower, to forget the face of your father is to act shamefully, or worse, to not have a sense of shame. And that’s exactly what modernity has stolen from us, exactly what we have lost when we can no longer hear the stories of our ancestors — our sense of shame.

From Sheep Logic (Oct. 2017):

The loss of our sense of shame is, I think, the greatest loss of our modern world, where scale and mass distribution are ends in themselves, where the supercilious State knows what’s best for you and your family, where communication policy and Fiat News shout down authenticity, where rapacious, know-nothing narcissism is celebrated as leadership even as civility, expertise, and service are mocked as cuckery. Or to put it in sheep logic terms: the tragedy of the flock is that everything is instrumental, including our relationship to others. Including our relationship to ourselves.

Why do we need shame? Because with no sense of shame there is no sense of honor. There is no mercy. There is no charity. There is no forgiveness. There is no loyalty. There is no courage. There is no service. There is no Code. There are no ties that bind us as citizens, as fellow pack members seeking to achieve something bigger and more important than our ability to graze on as much grass as we can. Something like, you know, liberty and justice for all.

A good shepherd once said that whoever shall smite thee on thy right cheek, turn to him the other also. Turning the other cheek always seemed to be kinda stupid to me. Kinda sheeplike. But then I started keeping sheep, and my perspective changed. Sheep would never turn the other cheek. But a wolf would. A wolf would take a hit for the pack. It’s the smart play for the long game. As wise as serpents, you might say.

It’s time to be wolves. Not as devourers, but as animals that know honor and shame. It’s time to be wise as serpents and harmless as doves. It’s time to remember the Old Stories. It’s time to find your pack.

Your family is your first and most important pack. It ultimately may not be your primary pack or your most supportive pack, but it is your first and most important source of that secure knowledge that you are loved and not alone, that you are valued intrinsically and not instrumentally, and that you should value others intrinsically and not instrumentally. Your family is where you first learn honor and shame, charity and obligation, independence and community, trust and loyalty … where you first learn what it means to be human. Not every family is a great pack. But every family IS a pack, and every family can be strengthened by preserving the stories and memory of those family members who radiate unconditional love, who live the lessons of honor and shame, charity and obligation, independence and community, trust and loyalty. This is a love and these are stories that are inconvenienced by death, but not broken! This is a love and these are stories that used to be the water in which we swim as human beings, where talking to a dead grandmother or feeling her presence in a completely real, physical sense was no more out of the ordinary than talking with a living grandmother.

Generative AI gives us the ability to remember the face of our father, to reclaim the familial stories that have been stolen from us by Science, the State and Capital, to celebrate a living relationship with our familial dead in a way that has been discouraged by the Abrahamic religions.

Generative AI gives us the ability to commune with our ancestors … at scale.

It’s not magic, and what I’m suggesting isn’t going to work, or at least not work well, with the already dead. I don’t think I’ll ever be able to have a satisfying conversation with my father because I doubt there’s enough text and unstructured data remaining from my father’s stories to capture his essence successfully today. I wish that I had prompted my father 30 years ago to write down his stories and his lore, but I didn’t.

I’m not going to have that same regret with my mother, still going strong in her mid-80s.

Yes, the best time to plant a tree is 30 years ago. The second best time is today.

What I’m going to do is collect the texts and unstructured data of my mother’s life — as best I can — and layer all that onto the structure of a modern LLM, so that the generic human response patterns made possible by generative AI can be imprinted with her personality, knowledge and beliefs. And not just imprinted in a static, recorded way, but imprinted so that new information — the photo of a newborn child, the parameters of an important life choice, anything I or my children would share with her today — can be understood and responded to with her essence and spirit when she’s gone.

Importantly, what I’m suggesting here — the creation of a generative AI totem like the figurines that Maximus uses to speak with his dead wife and son in Gladiator — is a step along the way of preserving, extending and resurrecting human consciousness, but only a step. The goal here is to commune with my mother after she’s gone, to receive comfort and advice through the lens of her unique personality, knowledge, beliefs and love for family, not to bring my mother back to ‘life’. The goal here is for my children and their children and their children to be able to access that unique personality, knowledge, beliefs and love for family in meaningful conversation, to receive a burst of the warm light I’ve bathed in all my life. The goal here is that over time … over a long time as I pass on and my wife passes on and my children pass on and so on and so on … our family of the future grows a forest of light and love and stories from us, their family of the past.

I think there are three categories of texts and unstructured data that must be collected in a comprehensive way to preserve my mother’s spirit for communion after death through generative AI.

1) Lore — the memories and moments, the people and places of a lifetime.

I’m not expecting my mother to remember all the formative events of a lifetime. I mean, I can’t even remember all the events of my life over the past month. But in addition to asking my mother specific questions about the most impactful people, places and events of her life, we can also reconstruct a timeline of her life — where she was and who she was with — with as much specificity as possible. Maybe that will be month to month, maybe year to year, maybe week to week. We’ll need to look through all those old photos she has in boxes somewhere. But if we know that my mother was, say, on vacation in Panama City sometime in the summer of 1956, we can expand that with generative AI to know what songs she would have heard on the radio, what the beach looked like back then, how long the drive back to Ft. Payne was, the news that might have filtered somehow into the consciousness of a teenage girl … a million potential memories that even if they’re not active memories are still part of what makes my mother a unique human being.

The ability of generative AI to expand a place or a date or a name into context is phenomenal, maybe the single most underappreciated superpower of the technology. It’s context that turns memory into lore, the specific knowledge that a pack uses to distinguish members from non-members, and it’s lore memory that will differentiate a believable conversation with my mother’s generative AI avatar from a non-believable conversation. I’ll never be able to access or record every lore memory of my living mother. But by on-demand expansion of the comprehensive context surrounding every conversational lore challenge, made possible by reference to a vector database of the people and places and events of her timeline, the generative AI imprint of my mother should have a believable response to every conversational topic that requires knowledge of the actual facts of her life. Combine this with her recorded memories of family lore (and recorded memories of other family members remembering my mother’s role in family lore), and I don’t think there’s a family Turing test that the AI imprint won’t be able to pass easily.

2) Beliefs — the story arcs by which a human makes sense of the world and their experiences.

If lore is the specific memories of people, places and events, beliefs are the general feelings about those people, places and events. The power of belief in imprinting a true essence onto a generative AI is found in this painfully true Maya Angelou quote.

I’ve learned that people will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel.

The questions I’m asking my mother to tease out her beliefs are not principally questions of fact or even context. They may call up and focus on a specific memory, often a specific person, but only to provide a vehicle for the description of feeling. Why? Because at the core of every story we tell — particularly the stories we tell ourselves — there is a feeling that motivates the story arc. Maybe it’s a feeling of love. Maybe it’s a feeling of fear. Maybe it’s boredom or pride or lust or greed, or maybe it’s adventure or generosity or hope or altruism. There are lots of feelings! But it’s always a feeling of some sort that is the engine of a belief structure and the story arc that follows that structure.

When I say I’m asking my mother questions to tease out her beliefs/feelings about the experiences of her life, I mean exactly that. I asked ChatGPT to come up with 100 questions along these lines, touching everything from childhood experiences to recent experiences in old age, each with a focal memory recollection that expands into an open-ended response opportunity. I want my mother to respond to each of these questions with as much text — both introspective (beliefs) and outwardly facing (lore) — as possible. She doesn’t need to type out her responses. I’m asking her to record her thoughts on the phone and we’ll get a transcript with otter.ai or similar. The important thing here is depth and breadth of unstructured text … as many questions as possible with as much answer as possible.

3) Adornment — the presentation and (re)presentation of a spirit.

I’m calling this set of unstructured data ‘adornment’ rather than ‘appearance’ because the generative AI essence or spirit of a loved one doesn’t really have an appearance. It really is an essence or a spirit. It really is a disembodied set of words and semantic connections. What we mean by appearance in this case is closer to skin, but that’s too gross. So I’m going with adornment, not least because there’s an element of choice here, too, as in how the spirit chooses to adorn itself with a skin and a voice and a physical appearance. All of which is malleable, of course.

There’s a wide range of commercial recording services out there today for digital avatar construction, and they’re honestly pretty amazing. We are well and truly through the uncanny valley when it comes to this stuff, and the price and latency of these digital avatars will continue to come down. I think it’s important to have a visual dimension to a communion totem, if not a tactile dimension, but I could be wrong about that. In any event, preserving my mother’s voice and appearance and mannerisms is a pretty trivial matter these days, and because she is an active participant in the process she can choose how she wants to be represented to her family of the future.

To be clear, I’m still figuring out how to put all this unstructured data together! This is absolutely a work in progress, and I can’t wait to see how people who read this note strike out on their own with ideas and implementations. One strong view I have on implementation, however, comes from my belief that we are creating a portrait of our loved ones, a living portrait that captures their essence, and that we would be well served to take our cues on implementation from the greatest portraitist in history, Leonardo DaVinci.

We’re all familiar with the Mona Lisa and how her smile communicates a depth of mystery in a few brushstrokes of oil paint, but probably less familiar with Lady with an Ermine. Look at the impossibly long fingers! Was Leonardo just not very good at painting hands? Well we know that’s not it. Were her fingers actually that long? Seems unlikely, but maybe. But now look at her smile and the way she’s looking and listening to something off canvas. Look at the expression of the pet ermine (which is way too large to be an actual ermine, btw). In the hands and the smiles and the expressions and the objects and the positioning and the movement Leonardo is painting the stories of these women, maybe reflected in ‘reality’ but also maybe not and who cares anyway. Leonardo is painting the stories that weave together lore and beliefs and adornment to present the essence of these women.

Here’s how Leonardo described his process:

A painter should begin every canvas with a wash of black, because all things in nature are dark except where exposed by the light.

Leonardo didn’t begin a portrait from a blank slate, a white canvas upon which he imposed his will and his vision, building up an image from its component parts. No, he began with a black canvas, where in Leonardo’s mind the essential image was already there, hidden by the black wash and waiting for the light. The genius of Leonardo was to reveal what was already there, not to create something new. Or to put it in terms of another art form, the process here is not to build a sculpture from scratch, but — as Michelangelo described it — to reveal a sculpture that was always ‘alive’ there within the marble.

I think this is such a profound truth for our process. I’m not building a robot of my mother, constructed from parts and never more than parts. I’m not writing the story of my mother, constructed from my words and never more than my words. My mother has already written her story. She is the artist here! She has already painted her stories in a glorious portrait, with pigments and hues and brushstrokes of a life well lived. It’s just that the pigment and hues and brushstrokes are hidden by a black wash right now, in the form of memories long forgotten, photographs in a shoebox, and questions never asked. All just waiting to be revealed by the light of love, time and care!

A generative AI system is a canvas washed with black for ALL of us, meaning that the portraits of all of our loved ones are already there in a modern LLM, meaning that all the ways in which a human spirit can present itself are already ‘alive’ as a potential persona within that generative AI canvas. It’s a canvas of infinite permutation, a block of marble that stretches out to infinity. Every unique human can create a unique imprint on generative AI, defined by their unique texts of lore, belief and adornment. This is how generative AI as a communion machine scales. This is how we change our entire society for the better, by strengthening each and every family from the bottom-up. This isn’t some expensive apparatus that only the rich can afford. There’s no ‘business model’ here with ‘defensible moats’ for private equity to salivate over. This is available to everyone willing to put in the time to talk and listen and write down the words — just that, talk and listen and write down the words! — of those relatives and loved ones who are the glue of your pack and might not be with us that much longer.

Nothing about communing with your dead loved ones will make you rich or powerful. And because there’s no money and no power in this project, only love and time and caring over a base of ubiquitous technology, nothing about this project will make sense to the Nudging State and the Nudging Oligarchy. That’s why they will ignore this, because it doesn’t play on their playground. And by the time they realize what a profound threat the inalienable and undying stories of our loved ones are to their stories … it will be too late to stop.

As a society, we used to remember the face of our fathers. And our mothers. And their fathers and mothers, and so on and so on, back generation after generation. We used to tell their stories. We used to celebrate their stories. It was our shield against the Hive.

And it will be again.

Gosh Ben, I’m struggling with this a bit. My recently deceased ancestors (past 40 years or so) of whom I have some actual memory are like most people in that they ALL had both praiseworthy traits and “warts”.

Like me.

The memories are all subjective at some level, and I’m not convinced that making those memories as objective as possible through GAI is ever going to capture the truth which I believe I KNOW - and choose to propagate - to our children. Does tasking GAI with providing an “accurate” description of an individual guarantee a legacy of our choosing?

I dunno.

My mortality is an accepted feature of life and occasionally thinking about that makes me behave better in the moment.

Would a GAI version of an individual be TRUSTED as accurate, or could it possibly be ignored as somehow manipulated? In today’s world of never ending conspiracies and data manipulation , IDK.

It’s funny Ben, because of my accident and injury, people share their stories much more freely with me than others. I think, because my portrait, the visual of my injury, tells most of my story before I have to fill in the details, they know I know pain and loss. I used to think it was so weird, perfect strangers would share very intimate, often sad and tragic stories minutes after meeting me. For a long time, I even felt guilty. Somewhere along the way, I began to realize exactly what you wrote, every one of the stories being shared, was in the smallest way, trying to keep a belief and a memory alive. It is sometimes the only thing that gets some through the next day, the next week, it simply gives people hope.

My Daughter Got Married September 28th, been thinking a lot about how being a quadriplegic dad impacted my daughters lately. Here’s 4 minutes that you can’t get back, of my 2 girls and a letter I didn’t think would be shared. Apologies for cluttering up the thread with a personal moment, but I’d love for it to live a few generations. #MayHaveCriedAlittle #SingularEvents

Thank you, Carl, for sharing your story.

Carl - that was the video that I didn’t know I needed and will always treasure. Story shared!

Beautiful and thought provoking piece.

I just came here to add that in reading Fustel de Coulanges’ The Ancient City (1864), one can argue that a key foundation of “property rights” emerged from the “property responsibilities” of maintaining the ancestral flame.

Binding these ideas together, I can’t help but consider the actual metal in which this new digital flame will reside, and what are the rights and responsibilities in owning and protecting this digital flame, right down to the metal? …and as the community will know soon, its exactly the hard problem I’ve been working on in digital identity and selfhood for about five years now with ID++ (and the storage of our personal, familial, and pack Echos).

Again, wonderful piece Ben,

/josh

I remember talking with you about this at our first Epsilon Connect!

A very moving post, and much of it rings true.

In theory the value of this technology is for the living. If we could go back and faithfully represent your father’s mind/essence, he wouldn’t know we had done so and it would make no difference to his life. The benefit would only be to us for knowing him better.

But because the technolgy exists, as it becomes known and used in this manner then it can benefit those who contribute their essences to know that they will have a lasting impact. How much better our final moments will be with the peace of mind that in a very real sense, our impact on the lives of those we love most does not end with our death nor even with theirs. We go on as long as there are others who have been loved and shaped by those we love.

Ben-

Thank you so much for writing this.

One note (or question or thought). When people used to commune with the dead, the person alive would ask the dead person for wisdom or an answer, and, unless they actually were speaking with the dead, the individual would seemingly discover, within themselves, the wisdom they needed to make a decision or to find their own answer. In other words, it was almost like a ritual that allowed them to internally deliberate and find their own “truth.” When you do this GAI thing, you seemingly remove yourself from the decision making function. You “outsource” the decision to the encapsulated wisdom (stripped of context) from those who have since passed. It’s less you, and more…Siri.

I think there is an absolutely immense amount one can learn through communing with the dead, or at least the ritual aspect of it. I think there is an absolutely immense amount one can learn in shutting of our hyper vigilant rational brain. I am very very wary of “purifying” or bottling wisdom into a thing, to cede an internal decision making process to something else. A mirage of what once was.

I hope this makes sense.