The skinny of “Pricing Power #1 – Client Ownership” is that pricing power in a services industry is found in your proximity to the client relationship, not the product that the client is buying. The problem, of course, is that it’s really really hard to scale client relationships, or at least it’s hard to scale the relationships that are worth scaling.

The skinny of “Pricing Power #2 – Intellectual Property” is something of the reverse. If you ARE on the product side of your industry, then the only way to maintain pricing power is through Narrative-rich if not mythic intellectual property. Conversely, relationship owners always think that they can scale their nice little client-facing businesses with Technology IP. They are always wrong. The one (rare) exception is the use of Content IP, but even here you are scaling your client relationship depth, not your client relationship breadth.

The skinny of "Pricing Power #3 - Government Collaboration" is that the most dependable way to protect your margins and maintain pricing power is to partner with the government to provide a politically useful service. I don't mean an overt partnership. I don't mean becoming a government contractor (although sure, that works, too). I mean identifying the social meaning of your services industry and implementing a business strategy that supports THAT.

I wonder if a similar value performance analysis has been done for corporate bonds over the past decade. I suspect that a ‘value’ based approach to bond investing may have been similarly disappointing as central bank largess has made debt access and service easier for the weakest of borrowers. It certainly compressed risk premiums. Inquiring minds…

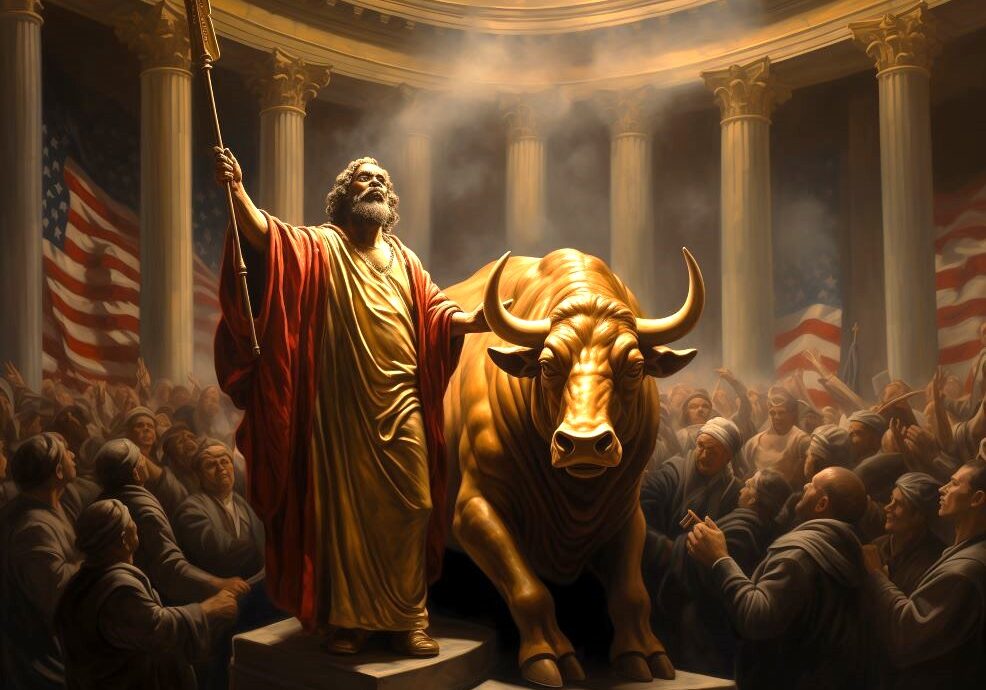

Those who regularly preach doom because of government budget deficits (as I regularly did myself for many years) might note that our country’s national debt has increased roughly 400-fold during the last of my 77-year periods. That’s 40,000%! Suppose you had foreseen this increase and panicked at the prospect of runaway deficits and a worthless currency. To “protect” yourself, you might have eschewed stocks and opted instead to buy 31⁄4 ounces of gold with your $114.75.

And what would that supposed protection have delivered? You would now have an asset worth about $4,200, less than 1% of what would have been realized from a simple unmanaged investment in American business. The magical metal was no match for the American mettle.

—Warren Buffet recently commented

“Until the plumbing breaks, and then suddenly, you can have a problem, because people have these mental models of how the world works and they’re actually wrong. And it matters, because you’re making policy decisions based on a false model.” —Peter Stella

https://www.mercatus.org/bridge/podcasts/02182019/peter-stella-debt-safe-assets-and-central-bank-operations

*Things to Think About:

If one extreme of the numbers/narrative spectrum is inhabited by those who are slaves to the numbers, at the other extreme are those who not only don’t trust numbers but don’t use them. Instead, they rely entirely on narrative to justify investments and valuations. Their motivations for doing so are simple.

Narrative-driven investing is not uncommon, especially with younger firms and start-ups, and I have been taken to task for even trying to value these companies using number-driven models. Paraphrasing some of the comments on my valuations of Twitter and Uber, the argument seems to be that while cash flow based valuations may work on Wall Street and with mature companies, they are not useful in analyzing the type of companies that venture capitalists look at. While it is true that rigid cash flow based models will not work with companies where promise and potential are what is driving value, staying with just narrative exposes you to two significant risks. The first is that, without constraints, creativity can carry you to the outer realms of reason and into fantasy. While that may be an admirable quality in a painter or a writer, it is a dangerous one for an investor. The second is that, when running a business as a manager or monitoring it as an investor, you need measures of whether you are on the right path, no matter where your business is in its life cycle. When narrative alone drives valuation and investing, there are no yard sticks to use to see whether you are on track, and if not, what you need to do to get back on the right path.

—Aswath Damodaran at Musings on Markets

Ike— a Morningstar study from 2017 (https://www.morningstar.com/blog/2018/05/23/bond-fund-fees.html ) showed that in all sub-categories the median bond fund failed to beat the respective index and, in fact, high yield and EM bond funds had the lowest likelihood of managers beating the index. The alpha simply can’t outpace the fees.

Thank you Robert. I found the next to last paragraph interesting in that they note that in the high yield market active management was superior because passive strategies focused on the most liquid (higher quality?) issuers. I guess where I’m going is that if you had structured a bond portfolio over the past decade you may have outperformed if you were overweight the poorest ‘quality’ debt in this central bank dominated environment. And if so, it begs the question ‘does it offer the same opportunity going forward’?

This is an interesting and important question. I think it’s difficult to generalize an answer but it MIGHT if you are cognizant of the risks and able to manage them effectively. This low-rate, policy-controlled environment incentivizes yield-chasing behavior. We see this very clearly in the explosion in private credit and leveraged loan strategies, as well as various permutations of “yieldy” short volatility strategies (whether explicitly shorting VIX instruments or by selling options, etc). Of course, the weakness of all “yieldy” strategies is that the risk/return profile is often very asymmetrical, in return for your fat yield you assume the risk of catastrophic losses (Feb 18 was a perfect example in the volatility space). My personal view is that if someone makes the decision to overweight super low quality debt it should be in the context of an actively managed strategy mindful of risk. In general I think what you see in the debt space is a fractal of the overall picture–risk has increasingly migrated from the “body” of the distribution of outcomes to the “tails.” Not sure whether this is helpful or just word vomit but maybe the added color is helpful in some way.

If NLP is the answer for active to recapture alpha what does that do for traditional style box investments? Or a better way to ask, if you’re using NLP to capture alpha the portfolio manager will need the flexibility to “go anywhere” correct?

This was a thought I had as I read this too. The value factor investors have taken it on the chin since the GFC and if that continues, at what point do we lose value factors as an investment style because no one wants to beat their heads against that wall anymore.?

We have to admit, this is progress. When banks failed in 1931, the Fed did nothing, and basically allowed the worst of the Great Depression to unfold. So, deflation was much more of the policy response than in recent times. (Only in 1933 was some inflation allowed, via devaluing against gold by 50%, over the objection of top bankers.)

The elites used deflation post-crisis, because they could. It was better than inflation for protecting the reputation of the money they issued. Democracy (and, I hate to say it, trade unions) made it impossible, later on, to make the public shoulder that much of the pain. (That was the true essence of Ben Bernanke’s ‘apology’ for the 1931 Fed policy!)

The failure of the gold standard, which had become total by 1971, was a good thing for holding gold, since the true nature of it was the open suppression of gold to a fixed currency price to help prop up the money and debt issued by the elites. (If you want a good dose of Common Knowledge or Narrative, how about the orthodoxy among economists of the time that the gold standard was superior and essential, on economic grounds?)

True, inflation has some features of theft or redistribution. It’s also the best of the bad alternatives after a bust. The wealth was never there in the first place, as soon as elite-driven Narrative had blown an asset bubble, so you could argue you’re only taking away from those foolish enough to believe in currency. Since bubble and bust are part and parcel of centrally-planned money, over the long term, inflation might even be celebrated, given the circumstances.

That is, with the exception of places like Greece and SE Asia, that are powerless to fight back against IMF-imposed post-crisis deflation.

Regarding Aswath Damodaran, you need both. You need narrative to decide which direction to go, and you need numbers to determine how far and how fast. They’re not mutually exclusive. But, true, you absolutely don’t want to worship one of them exclusively.

At the risk of appearing to pick on an old man, you would never expect Buffet, a poster-child beneficiary of imperial asset inflation and a recipient of the Medal of Freedom to say good things about gold, at least not after the imperial elites have officially abandoned the gold standard. Gold shouldn’t be compared against stocks since the money you bet on the ‘prosperity’ scenario should never be used to buy gold anyway. Gold should be compared to debt-free, risk-free assets, and the best candidate among these is dollars under the mattress. In this comparison, cash has lost 97% of its value, over the 77 year span.

Totally see it same way with additional supporting comments. It’s probably not a coincidence that after REG D and the mark to market risk in public securities that the trend to invest in the private markets has continued to accelerate. The sixty forty mix over this time has seen the 60% equity go to around 42% public and 18% private from virtually zero private. This is where research can still add value and with new money flowing in, that rising tide of private security investing has turned into a flood. When Uber IPO’s at 50 Billion, the smart institutional money will sell their private shares to the institutional buyers who are mandated to stay in public markets and the indexers. The easier money will have been made (it’s still hard no matter what). Probably also helps that private markets are much more SEC friendly for every player. Of course, I suspect the Regulators will turn on that some day in order to increase their reach. They follow the money, too.

The last area where active research in public markets can be effective is microcap stocks. It’s too small for sell side research to cover and not big enough for asset managers to sustain a fee paying business model. However, microcaps are semi-publicly traded. They are more like publicly listed private equity. Caveat emptor unless you have better information than other players in the space.

I miss the old Mandarin Oriental days. In the 90’s, our local CFA chapter would have three analyst meetings a week from CEOs and CFOs of companies that you’ve heard of. No more Mandarin. It’s a Loews.