Every morning, we run the Narrative Machine on the past 24 hours worth of financial media to find the most on-narrative (i.e. interconnected and central) stories in financial media. It’s not a list of best articles or articles we think are most interesting … often far from it. But for whatever reason these are articles that are representative of some chord that has been struck in Narrative-world. And whenever we think there’s a story behind the narrative connectivity of an article … we write about it. That’s The Zeitgeist. Our narrative analysis of the day’s financial media in bite-size form.

To receive a free full-text email of The Zeitgeist whenever we publish to the website, please sign up here. You’ll get two or three of these emails every week, and your email will not be shared with anyone. Ever.

We use the term Cartoon a lot. Perhaps some definitions are in order.

When we call something a cartoon on Epsilon Theory, what we mean is an active attempt to create Common Knowledge about what a thing means, or alternatively what matters about that thing. When Nike embraced Kaepernick, they actively sought to create polarized knowledge about what buying Nike products or stock meant. They succeeded. I’d argue that Chick-fil-a has done the same, albeit somewhat more subtly. In our own industry, Vanguard has done this, too, by cultivating a belief that index investing was a synonym for low cost investing. It isn’t.

Yes, brand is a kind of cartoon.

There are other kinds of cartoons, too. Not every company is a consumer product company for which a polarizing political statement will have the effect that Nike’s did. Instead, these cartoons exist in financial terms. The company doesn’t tell you what their brand means. Instead, they tell you which metric about their company or stock really matters. It’s a tougher game to play, because – at least superficially – there are theoretically people who couldn’t care less what management thinks. Back when they still existed, we called these people ‘value investors.’ But the whole game of cartoons is the creation of common knowledge – what everyone knows that everyone knows – and even if you know that cyclically-adjusted net unique monthly eyeballs is not a Thing, your own time horizons as a fund manager / analyst probably won’t permit you to ignore the two layers below you in the Keynesian Beauty Contest that believe that everyone else believes it is a Thing.

The “Top Line” cartoon is a simple, successful example of this kind of thing. So long as the underlying products – and sources of cheap capital – support it, the Top Line cartoon can be sustained for a very long time. Many of the other examples (we usually pick on Salesforce.com) look far more like examples of reductio ad absurdum than the Top Line cartoon’s gentle story-telling. The tell-tale signs, I think, are esoteric, business-specific metrics or accounting treatments over which management has substantial control and the public limited visibility.

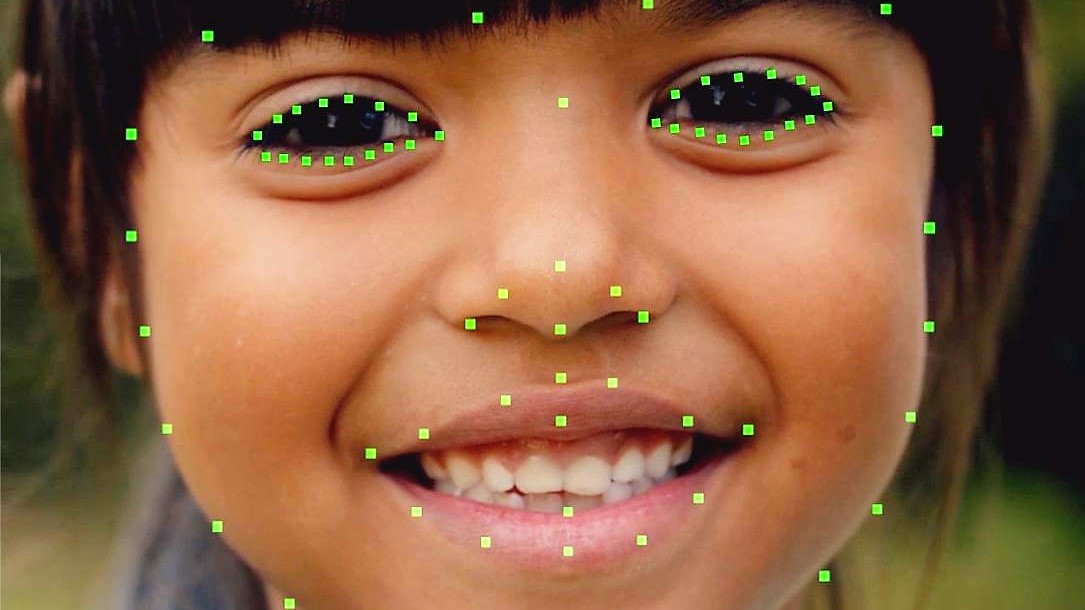

The language of these cartoons is, in fact, so indicative that our own NLP analysis tends to arrange guidance, statements and financial results from heavily cartoonified companies into very distinct clusters. These are the articles which don’t so much publish management’s discussions about the business or financial results as much as they do about the measures being promoted by management (or in some cases, the sell side) as the right way to understand that company’s results.

The success of cartoon management has been such that these clusters have grown to dominate the news and company-produced content in many of the economic sectors we track. This is part of the zeitgeist. And today, it is really part of the Zeitgeist. To wit, the second most closely connected article to all other financial markets articles published in the last day or so comes from an industry that is almost entirely built upon a foundation of cartoon management.

Aurora Cannabis’ Guidance Was ‘Manna From Heaven’, Cannabis One CEO Says [The Street]

It’s a short video and a short article, but if you grew up listening to earnings calls in which management teams protested their indifference to short-term opinions floating around the market in favor of long-term growth opportunities, you’ll be delighted to hear how this has changed. Manna from heaven isn’t a monumental growth opportunity or a phenomenal new product or research breakthrough. Manna from heaven is now the relaxation of negative short-term narrative pressures on stock price.

The number three article in our ranking this morning is a defense of one of the oldest forms of cartoonification – the clever use of accounting to present results in a particular light. And so it is linked to all those other cartoon-creation articles by language. What language? Misleading. Accounting. Inflated. Adjusted. And “reaffirmation of guidance”, a precious term which often seems to cover all sins.

Australia’s Treasury Wine rejects report alleging it inflated profit [Reuters]

And when the belief in a cartoon fails, how far can you fall? Pretty far. This is the fifth most connected article in today’s Zeitgeist run (and for those inevitably curious at what I skipped over today, it was an Art Cashin “whistling past the graveyard” piece and a Cramer “what I learned from soft pretzels” article – you’re welcome).

Care.com Founder to Step Down as CEO Months After WSJ Report [WSJ]

No, of course cartoonification doesn’t always mean taking a creative interpretation of inventory accounting rules or their application. It doesn’t mean fraudulent representations about fundamental business practices. Sometimes it really is just telling people “the right way” to think about your company, product, results, or even yourself. For that reason, we think that anyone and any company who doesn’t see controlling their cartoon as part of their job is making a mistake. Narrative isn’t evil, even if it is used a vessel for many evils.

But much of the impulse behind cartoon creation is the same as the impulse behind other drivers of the Long Now. It is behind what some of us unserious people mean when we insist on using the term financialization. No, not the idiotic meme of “things mean rich people do to make money for shareholders instead of supporting this social value I hold!” We mean the things which people allocating capital have incentives to do because those incentives align with maximizing the current perception of value rather than actual long-term value.

Financialization – again, in our own use of the term – is little more than a belief that there are incentives to deploy capital and labor resources to ends other than long-term value creation, that our present always-on media, social landscape and transformation of financial markets into political utilities aggravate those incentives, and that this might be bad.

The Long Now is how this tendency permeates not only financial markets but our personal financial decisions, friendships, life decisions, political engagement and cultural participation.

Cartoons are the engine behind both.

Clear Eyes – control your cartoon.

Full Hearts – control the extent to which controlling your cartoon may be keeping you from pursuing things of lasting value.

Hey Rusty, love everything you write but please don’t send us to articles by WSJ where we need to spend $100 for a subscription. One might think that they would have developed BAT token acceptance or micropayments for access to an article now and then.After all, they are not Communists!

Hear ya, Bob, but I hope you can see why trying to evaluate the zeitgeist of financial news without any use of the WSJ might present an unfortunately incomplete picture!