Download a PDF copy of The Four Horsemen of the Great Ravine, Part 1 (paid subscribers only).

Every so often, things fall apart.

Every so often, human society collapses into violence both economic and kinetic, both large-scale and small-scale, a war of all against all where life is nasty, brutish and short.

I can’t shake the feeling that we are beginning just such a descent, a winding but one-way path down, down, down into what my favorite living author, Chinese science fiction writer Liu Cixin, calls the Great Ravine.

Maybe it’s just the grumpy old man coming out in me, but I’ve always believed that there is a process and a pattern and a lifecycle to any human society. I’ve always believed that part of that lifecycle is decline and collapse. I’ve always believed that there would be recognizable signs and portents for that final stage, signs and portents that I think I’m seeing now.

It’s not that I think history repeats itself, but I definitely think it rhymes. And if I’m right, if we are today starting down a well-trod human path to social collapse, then there’s nothing more important than figuring out the rhyme of history.

The rhyme of history is where we find meaning from our past to provide wisdom for our future.

If you’re familiar with old school historians like Gibbon, Toynbee and the Durants, you’ll know what I’m talking about because the lifecycle and rhyme of history is what they write about. These old school historians are out of favor in academia these days, which is a shame, because they can turn a phrase like nobody’s business, like this from Gibbon writing about the lawfare and warfare between a succession of dueling Roman emperors and their supporters in the middle of the third century AD:

Such, indeed, is the policy … severely to remember injuries, and to forget the most important services. Revenge is profitable, gratitude is expensive. – Edward Gibbon, The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Vol. 1 chap XI pt 2 (1776)

I love this quote from Gibbon for the same reason that I love so many quotes from the Durants … it’s communicating a vibe from the third century AD, a vibe that I recognize so clearly in the twenty-first century AD.

I mean, if there’s a better description of our national ‘leaders’ today than a profound commitment to injury-remembering and service-forgetting and score-settling, and yes I’m very much talking about Trump and crew but I am also very much talking about Biden and crew, then I am unaware of what that description might be.

What does it mean to say that history rhymes? This! The rhyme of history is found in the vibes that connect one society at a point in time to another society at another point in time, in the expressions and motifs of meaning that connect human cultures across time and space.

I know this all sounds very touchy-feely, very un-scientific to talk about vibes and feelings and motifs of meaning and the rhyme of history, but it’s not. All of these touchy-feely words are part of the science of semantics — the exploration of meaning in information and communication. Generative AI and large language modeling are 100% based on semantic theory, and if we get nothing else from our advances in those fields over the past few years, we should get this: the invisible world of semantics is just as real as the physical world, and just as there is a unique signature to every chemical element in the physical world, so is there a unique signature to every embedded linguistic pattern of meaning in the semantic world.

Yes, Gibbon is communicating the vibes of the third century AD. More precisely, Gibbon is communicating the semantic signatures of the third century AD, embedded elements of social meaning that he parsed from his reading of the texts describing that ancient Roman world.

Why is it so important to think of history – particularly the patterns and the lifecycle and the rhymes of history – in terms of semantics and embedded linguistic elements of social meaning?

Because it allows us to apply directly the tools of generative AI and large language modeling to primary historical texts at incredible scale and scope, making historical interpretation and meaning-finding available to everyone rather than remaining the province of academic historians or the plaything of revisionist politicians.

See, as much as I appreciate Gibbon and Toynbee and the Durants as gifted storytellers, I don’t entirely trust them to relate historical vibes and semantic signatures faithfully. Sometimes for better but often for worse they’re quick to present their specific cultural sensibilities as eternal human truths. For example, Gibbon was very dismissive of religion in general and Catholicism in particular, and I think this absolutely colored his take on the impact of Christianity on the Roman Empire. And if I don’t entirely trust Edward Gibbon or Will and Ariel Durant as faithful semantic reporters, imagine how little I trust the ‘lessons of history’ from woke Yale historians or MAGA billionaires!

No, instead of looking to ideologically-captured historians or political party suck-ups or centibillionaires looking for the next big score, I think we’re better off looking to primary historical sources, broadly defined. I think we should look to the contemporaneous rhyme of history — the vibes and the semantic signatures of history as related in texts by writers who were actually there.

After all, what is a vibe but a plucking of an invisible string of thought in the invisible world of meaning/semantics … a vibration of that invisible string in that invisible world that we ‘hear’ as a feeling about the ‘real’ world. For thousands of years, humans have written these feelings down as we are experiencing them. We write them down in books and plays and poems and essays and letters, we write them down in a thousand different ways and structures and mediums. These are the unstructured texts of history, the primary sources of history even if they’re not intended to be an historical account, because embedded within these words are the semantic signatures that represent our feelings and our vibes and our motifs of meaning within our particular human culture in our particular time and space.

Ultimately, I think we’re on the cusp of an entirely new way of understanding history and political science, where we use generative AI to uncover the semantic signatures of storytelling texts written by people who lived in and through the events we want to understand, and then – also using generative AI – we reconstruct a comprehensive, truthful-in-its-time narrative of the period in question from those primary-sourced semantic signatures.

I believe that we can take the true primary texts of human history – our novels and plays and poems and religious texts and fables and folk tales and diaries and letters – and tease out their linguistic threads and motifs of meaning (semantic signatures!) in order to weave a better human history, impervious to the collectivist, anti-human, history-rewriting impulse of the Nudging State and Nudging Oligarchy.

More than anything else, this gives me hope that we can survive and shorten our Great Ravine, that we can use generative AI to build an effective defense against the retconning and Orwellian rewriting of history that is the most powerful enemy of humanity.

This is the Great Project of my life. No biggie.

For today, though, I just want to give you a taste of what’s possible in a semantic approach to historical understanding even without large language models and generative AI, as we seek to understand the process by which a society descends into madness.

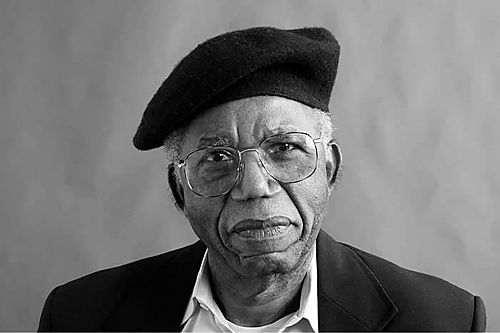

I’ll start with Chinua Achebe and his novel about how things fell apart in Southeastern Nigeria, a social decline and collapse that resulted in the Igbo/Biafran independence movement and civil war of 1967-1970.

Achebe’s words lead us directly to William Butler Yeats and his poems of the descent into World War I, known at the time as The Great War and The War to End All Wars. It wasn’t.

Yeats’s words in turn take us to the essays of Hannah Arendt on the social origins of World War II. Yes, you could call Arendt a historian and a philosopher, but her most powerful work is as a direct observer, a chronicler of contemporaneous events.

From there I’ll look to the stories of science fiction writer Liu Cixin, who writes of a global collapse in some far-off future – what he calls the Great Ravine – as a way of describing the vibes and semantic signatures of the Cultural Revolution.

Four gifted storytellers who lived it, who can relate the vibes and the semantic signatures of some of the twentieth century’s most devastating social collapses.

And from the meaning in their words, wisdom for our future emerges.

image: Paris Review, winter 1994

In 1958, Chinua Achebe published Things Fall Apart, a novel about the collapse of traditional Igbo society in Southeastern Nigeria under the weight of colonialism and Christianity, a social decline and collapse that ultimately resulted in the Biafran War of 1967-1970.

This is the least disturbing photograph I could find of the Biafran War, which the Nigerian government won by imposing a blockade and starving somewhere between 500,000 and 1,000,000 Igbo civilians to death. I think about this sometimes when the African Union and the Nigerian government start talking about a ‘genocide’ in Gaza.

“The white man is very clever. He came quietly and peaceably with his religion. We were amused at his foolishness and allowed him to stay. Now he has won our brothers, and our clan can no longer act like one. He has put a knife on the things that held us together and we have fallen apart.”

Achebe doesn’t sugarcoat the pre-colonial, pre-Christian Igbo clans in Things Fall Apart. Like most traditional societies, they’re hidebound and intensely patriarchal and cruel by modern standards. But it is not a casual cruelty. There is honor in the clan, there is an authentic community in the clan, there is a social good in the clan.

A man who calls his kinsmen to a feast does not do so to save them from starving. They all have food in their own homes. When we gather together in the moonlit village ground it is not because of the moon. Every man can see it in his own compound. We come together because it is good for kinsmen to do so.

But colonialism and Christianity were only the catalysts of social decline and collapse. Long before the white man came onto the scene, the villages and clans of Achebe’s world had already forgotten the WHY of their traditions and their institutions of cooperation.

Ogbuef Ezedudu, who was the oldest man in the village, was telling two other men when they came to visit him that the punishment for breaking the Peace of Ani had become very mild in their clan.

“It has not always been so,” he said. “My father told me that he had been told that in the past a man who broke the peace was dragged on the ground through the village until he died. But after a while this custom was stopped because it spoiled the peace which it was meant to preserve.”

Igbo society falls apart into honor-less, community-less, petty strife of every man for himself, not so much because of what colonialism and Christianity do to the Igbo, but because of what the Igbo do to themselves.

Yes, the economic/military power of neoliberalism colonialism and the ideological power of MAGA/wokism Christianity demolished the empty shells of American Igbo traditions and institutions of cooperation.

But the real tragedy of Things Fall Apart is the hollowing out of those traditions and institutions in the first place, and the emergence of intensely selfish and flawed American Igbo leaders as the old ways are dismantled around them.

Perhaps down in his heart Okonkwo was not a cruel man. But his whole life was dominated by fear, the fear of failure and of weakness. It was deeper and more intimate that the fear of evil and capricious gods and of magic, the fear of the forest, and of the forces of nature, malevolent, red in tooth and claw. Okonkwo’s fear was greater than these. It was not external but lay deep within himself.

Six years ago I wrote a series of notes called Things Fall Apart, my homage to Achebe’s novel and my first effort to rhyme his patterns of social collapse with our patterns of social collapse. Here’s the money quote:

How did we get here? We got soft. I don’t mean that in a macho sort of way. I don’t even mean that as a bad thing. I mean that, just like the Romans of Gibbon’s history and just like the Africans of Achebe’s novel and just like the mobsters of the Sopranos, we have long forgotten the horrors of literal war and why we constructed these cooperatively-oriented institutions in the first place. We are content instead to trust that the Peace of Ani or the Peace of the Five Families or the Pax Romana or the Pax Americana is a stable peace – a stable equilibrium – where we can all just focus on living our best lives and eking out a liiiiitle bit of relative advantage. We are content to become creatures of the flock, intently other-observing animals, consumed by concerns of relative positioning to graze on more grass than the sheep next to us.

Besides, it’s so wearying to maintain the actual intent of the old institutions, to mean it when you swear an oath to a Constitution or a god or a chief, and not just see it as an empty ritual that must be observed before getting the keys to the car.

If it weren’t Trump, it would be someone just as ridiculous. It WILL be someone just as ridiculous in the future, probably someone on the other side of the political spectrum, someone like Elizabeth Warren or Kamala Harris. See, I am an equal opportunity connoisseur of ridiculous politicians.

Things Fall Apart, Part 1 (August, 2018)

I wrote this before Kamala Harris was a blip on the Presidential radar screen. Good guess, right? But if you read Achebe, it’s not a guess at all. It’s obvious where all of this is going. Men and women of honor recede into the background, and ridiculous, profoundly flawed ‘leaders’ come to the fore. This, like the injury-remembering and service-forgetting and score-settling noted by Gibbon, is a semantic signature of a society as it descends into madness and violence, as true for Americans today as it was for the Igbo in the 1950s.

Or for Europeans in the 1910s.

image: Chicago Daily News negatives collection, Chicago History Museum

Achebe took the title of his book from a 1919 poem by William Butler Yeats, The Second Coming, where Yeats describes the collapse of Western society in the lead-up and progression of World War I. Here’s the stanza that gave Achebe the title for his novel:

Turning and turning in the Widening Gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

Every phrase in this poem represents a semantic signature, because that’s what poetry is — a distillation of semantic signatures into their 120-proof forms — and W.B. Yeats is one of the preeminent distillers of semantic spirits in human history. And yes, there’s an Epsilon Theory note on that:

Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

We are the falcon, and the falconer is … God, if you’re religious, the Old Songs of reason and empathy and reciprocity if (like me and like Yeats) you’re not.

In the widening gyre, we are deafened by Big Media and its New Songs of schadenfreude and I-got-mine-Jack, unable to hear the precepts of our better natures or the lessons of the past.

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

The widening gyre is political polarization, where a mad rush to more and more extreme positions is the dominant political strategy, presided over by the institutionalized, unquestioned power of Big Politics.

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

There’s no escape from the widening gyre! Big Tech brings mere anarchy – quotidian, ordinary, boring anarchy – to every aspect of our daily lives, so that all of our social ceremonies of association and friendship – all of them – are drowned in a relentless, implacable tsunami of “news” and “social media”.

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

The widening gyre is Gresham’s Law, not for money but for people and ideas. The widening gyre is a profound social equilibrium where bad people and bad ideas drive good people and good ideas out of circulation. It is the triumph of Fiat World, where Fiat News and fiat ideas and fiat people are presented as reality by proclamation, not lived experience.

The Widening Gyre (Sept. 2022)

And don’t get me started on the second stanza of the poem! Where a line like Slouches towards Bethlehem inspires with its semantic signatures of Armageddon and corruption, especially with the pure, raw, lethargic but murderous movement of that genius word ‘slouches’.

Just as Achebe wrote an entire novel based on the phrase Things fall apart, I’ve written so many notes on the phrase the Widening Gyre, which I believe is the essential distillation of political and social polarization as an equilibrium, a universal semantic signature of social decline and collapse.

But as crucial as the vibe of a widening gyre is for understanding the historical rhyme of social collapse, it’s another line I want to focus on now, because I think it represents an even more powerful semantic signature of decline.

Mere anarchy. What a phrase!

The ordinariness of anarchy, the ho-hum of humans losing their humanity, what Ionesco described as “oh look, another Rhinoceros” in his absurdist play by the same name … THIS is the semantic signature of social collapse that I was not expecting in my reading of the storytellers who lived it.

And no one has written in that motif of meaning better and with more clarity than Hannah Arendt.

photograph by Ryohei Noda (CC BY 2.0)

In 1961, Arendt went to Jerusalem to watch the trial of Adolf Eichmann, the foremost architect of Germany’s Final Solution, its industrial-scale strategy in World War II to exterminate millions of Jews and other ‘undesirables’. Eichmann had fled Germany for Argentina at the end of the war, where he was captured by Mossad agents and taken to Israel for trial (there are several movies about that search and capture operation, as it makes for a classic Hollywood spy thriller). Eichmann was convicted of crimes under Israel’s Nazis and Nazi Collaborators Law, and was hanged in 1962 in the only example to date of judicial capital punishment in Israel.

In 1963, first in a series of articles for The New Yorker and then in a standalone book, Arendt published Eichmann in Jerusalem, her take on the man and the trial. Arendt, a German Jew whose resume included an arrest by the Gestapo in 1933 and an escape from a French concentration camp in 1940 before securing forged identity papers to get first to Portugal and then to the United States, wrote that she expected Eichmann to be larger than life, a metaphorically towering figure who would emanate evil like a charismatic devil. Instead she found a nebbish. Instead of a larger than life character she found a smaller than life man. Instead of the visionary architect of State-directed evil on an unimaginable scale, she found the managing director of State-directed evil on an unimaginable scale.

In Hannah Arendt’s words, Adolf Eichmann personified the banality of evil, the quiet managerial tedium and ordinariness by which our world descends into madness and violence.

For me, Arendt’s banality of evil is second only to Yeats’s widening gyre as a potent distillation of a semantic signature about the path of social decline. This is a historical rhyme of the Great Ravine that rings and rings. Even if to many it is intensely unsatisfying.

Arendt’s essay on Eichmann’s trial and the banality of evil has been heavily criticized over the years, primarily because she doesn’t make Eichmann enough of a supervillain. He’s an anti-Semite and a monster, sure, but it’s not his anti-Semitism and his monstrousness that made him an S-Tier evildoer, the murderer of millions of human beings. No, Eichmann’s effectiveness at doing evil came from his managerial smarts. It came from his keen ability to work with symbols and numbers and schedules and spreadsheets and meetings and planning documents. Yes, Adolf Eichmann was an evil dude, AND his infamy is not because he was an evil dude, but because he was a highly effective industrial manager in a system that was doing evil on an industrial scale. He was the director of the OG department of government efficiency, enthusiastically being really efficient at the industrial murder of millions. And that’s so boring. There’s no story to Adolf Eichmann’s infamy other than that there is no story, and that’s why Arendt gets dismissed as ‘not being hard enough’ on Eichmann or ‘letting him off the hook’ or ‘blaming the victims’.

We desperately want the evil things that happen in this world and the evil people who do them to have a story, so that our suffering through that evil has some purpose, that it somehow advances the plot to endure evil.

But it doesn’t. It’s just not true. The collapse of a society into selfish violence isn’t a story of supervillains, strutting and monologuing their way through Act II so we can get to the superhero victory of Act III. It isn’t a story at all. There’s no plot here. No triumph. No redemption on a grand scale. No overcoming of anything. It’s only pain.

I learned this from the science fiction novels of Liu Cixin, after I finally realized that they’re not science fiction.

I mean, of course Liu’s work is science fiction. The Three-Body Problem trilogy is the most inventive and inspiring science fiction I’ve read since Asimov. AND it’s not science fiction at all. AND it’s a lived it account of seeing your parents sent to the mines during the Cultural Revolution, of seeing the damage of the Cultural Revolution never really going away but just being absorbed and forgotten over time. Liu conveys this account directly in the first chapters of Three-Body Problem, where he writes about the Cultural Revolution and its impact on everything that happens afterwards, and he conveys it indirectly in later chapters that take place in the far future.

In The Dark Forest, volume 2 of the Three-Body Problem science fiction trilogy, Cixin Liu mentions almost in passing a 50-year period of immense social upheaval, destruction and (ultimately) recovery across the globe. He never goes into the details of this period that he calls the Great Ravine. He basically just waves his hands at it and writes “yep, that happened”.

Why? Because the Great Ravine does not advance the plot.

It’s there. It happens. But there’s nothing to be gained by examining its events. Like the Cultural Revolution of Cixin Liu’s real-world history, the Great Ravine is ultimately just a tragic waste. A waste of time. A waste of wealth. A waste of lives. There is nothing to be learned from our time in the Great Ravine; it must simply be crossed.

This is the Great Ravine (July, 2024)

The Great Ravine is not permanent, but it’s not a Fourth Turning or a cyclical thing, either. There is no plot line here! And that’s what a cycle is … a plot line, a script.

Eventually we find our way out, but it can take decades for humanity to claw its way out of a Ravine. Longer, even. I mean, Gibbon tracked the decline and fall of the Roman empire over centuries, and the Dark Age was literally that … an Age. I don’t think we have the semantic signatures for this notion of being plot-less for an indefinite period of time, of being adrift in a world of learned helplessness, casual cruelty, petty tyranny and industrial-scale evil without a story to give us direction. How do we recognize our place in this process of … wandering … and how do we find a story to guide us through? On this the stories of Achebe, Yeats, Arendt and Liu are silent.

To be sure there is wisdom in the semantic signatures of our four authors as they relate their stories of social decline and collapse around the Biafran War, World War I, World War II and the Cultural Revolution.

From Achebe, the Great Ravine is catalyzed by ideologies, guns and money that shred the hollowed-out old ways, leading to the internal emergence of petty, selfish tyrants at every level of society.

From Yeats, the Great Ravine is a widening gyre, a process of polarization that is not mean-reverting but expands until the world inevitably breaks.

From Arendt, the Great Ravine is not created by supervillains of evil purpose but by completely ordinary villains who operate the industrial machinery of the small-f fascist State with great efficiency.

From Liu, the Great Ravine is plotless and empty of redemption, where politically-motivated stories of magical thinking capture the Mob and create pain without purpose.

All of these are powerful insights for our present day. All of these are rhymes that, for me at least, resonate strongly with what I see happening in our world.

But what I’m missing is the rubric that weaves these semantic signatures into a coherent whole. I’m missing the rhyme scheme, the semantic blueprint that reconstructs these linguistic motifs of social meaning into a complete story arc. But for that I need an author who somehow exists across time and place, who somehow relates not just the vibes of a particular point in time but ALL the vibes.

Perhaps the answer is to look not for a single author but for a set of authors. If only there were a text written by a set of gifted storytellers with a unified purpose across time and place, not written as history per se but imbued with history nonetheless.

How do we recognize where we are as we wander down and through the Great Ravine? How do we maintain hope even if there’s no apparent plot to advance?

I think the Book of Exodus has something to tell us about that.

I think the Bible as a primary historical source contains the ur-semantic signatures of ALL of this, from our initial descent into the Great Ravine to our wandering through it to our eventual climb out of it, and in Part 2 that’s where I’ll look for the rhyme scheme to place the semantic signatures of twentieth-century social conflict and collapse into a story arc of meaning for the twenty-first.

In Part 1 I think we found insight for our present.

In Part 2 I hope to find wisdom for our future.

I get the meaning, I think. He is observing a tension between short-term comfort or concord and long-term meaning, purpose, or narrative of a village.

And, cranky hidebound old people of every generation tell Just So Stories like this, recorded back to Roman times, no? Many of them to the modern ear are clearly ridiculous or at least incomplete and based on revised memories. “When I was your age I used to walk 6 miles to school each way in the snow and we didn’t have the Internet and so now all the kids are lazy and fat!”

Independent of the problem of motivated historians, I’m curious how/if LLMs can tease out some fundamental distinction of the vibes here.

(I have changed my mind about generative AI. In part because I have learned to use ChatGPT to save some time and money on some business stuff. BUT, what hooked me was AI not as nebbish but as bard: when my brother stayed over this Christmas and, in a matter of hours and without any prior AI knowledge, learned prompting enough to create beautiful absurd art with DALL-E based on the imagination of my 3-year-old.)

Ben, are you sure you have never been to 1887 and commissioned a painting?

What would that painting look like in the context of our higher-technological society?

I don’t care about the [insert famine icon] (famine), syringe (pestilence), missile (war), mushroom cloud (death), but the word.

If it would show a microphone/camera more than a keyboard, then the word has lost its communication supremacy to a coalition.

Words are cheap, quality film clips aren’t.

I think GPT40 did a pretty good job of extracting the Semantic Signatures of Ben’s piece. I need to use this miracle tool more often.

ChatGPT:

The semantic signature of the PDF, “The Four Horsemen of the Great Ravine, Part 1” by Ben Hunt, is rooted in a set of recurring motifs that capture the author’s exploration of societal collapse, historical patterns, and the loss of meaning within institutions and culture. These embedded themes reflect a worldview that societies follow predictable paths of decline and fragmentation, often catalyzed by internal weaknesses rather than external forces.

Here are the key semantic motifs that make up its signature:

The document’s core semantic signature can be described as:

It blends themes of existential wandering, political polarization, and institutional decay, while advocating for using semantic tools to preserve historical truths and find wisdom in the past for future resilience.

Pretty wild, right? Once you start applying this semantic lens to texts, you can’t stop!

It is still more enjoyable to read from a human source versus links of silicon/gallium arsenide or whatever the new chips are made from…

Great writing. Really hits home on a day like today when I am told my country will be forced to be annexed by the US or else. Keep it up!

A thing I cannot resolve here and I think is a mild contradiction:

Did a big prior Great Ravine, say 1914-1945, advance the plot? Was there nothing to be learned from the world wars? Alternatively are they somehow not a GR? It sure was a time of great waste, but contra the idea that there’s nothing to be gained on examination, I tend to think of 1914-1945 as almost its own century that followed on after the long 19th, but I also think it’s the most proximate real event we can describe as a Great Ravine.

In The Dark Forest, the Great Ravine clears out a bunch of the plot undergrowth that came before and is sort of a plot jump discontinuity for the humans on Earth. I think it almost has to be elided in the trilogy or it would require its own entire book worth of digression from the core Human/Trisolaran/Dark Forest denizens plot.

Unfortunately, we don’t have the option to fast forward it. We’re going to be around for the breaking and remaking of the world.

I think that’s right! And as you say, we don’t have the option of fast-forwarding through the next 50 years.

As for whether we ‘learned’ anything from the World Wars … I really don’t think we did! I don’t think there was any plot advancement there at all. That’s what I was getting at especially with Yeats, who wrote The Second Coming not just as a reaction to The Great War but also the Russian Revolution and - particularly important to Yeats - the Easter Rebellion. There’s no throughline there, just madness and death.

Is it adequate explanation that most people who were adults during this period are now dead or senile? Reading about things abstractly in school is very different from living and remembering them.

Setting aside the technology changes - I think you must be right. We didn’t learn anything about ourselves that we couldn’t have already known, but…

The people that lived through it learned how to cooperate and spontaneously de-escalate, to go from rhino back to human being, and also to build institutions and tell stories that encouraged that behavior instead. The nuclear war close calls from the 50s-80s are pretty much this, in the extreme case, IMO. But yes, just about everyone who remembers how bad things got are dead now, so we have to repeat the cycle.