DISCLOSURES

This commentary is being provided to you as general information only and should not be taken as investment advice. The opinions expressed in these materials represent the personal views of the author(s). It is not investment research or a research recommendation, as it does not constitute substantive research or analysis. Any action that you take as a result of information contained in this document is ultimately your responsibility. Epsilon Theory will not accept liability for any loss or damage, including without limitation to any loss of profit, which may arise directly or indirectly from use of or reliance on such information. Consult your investment advisor before making any investment decisions. It must be noted, that no one can accurately predict the future of the market with certainty or guarantee future investment performance. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results.

Statements in this communication are forward-looking statements.

The forward-looking statements and other views expressed herein are as of the date of this publication. Actual future results or occurrences may differ significantly from those anticipated in any forward-looking statements, and there is no guarantee that any predictions will come to pass. The views expressed herein are subject to change at any time, due to numerous market and other factors. Epsilon Theory disclaims any obligation to update publicly or revise any forward-looking statements or views expressed herein.

This information is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation of any offer to buy any securities.

This commentary has been prepared without regard to the individual financial circumstances and objectives of persons who receive it. Epsilon Theory recommends that investors independently evaluate particular investments and strategies, and encourages investors to seek the advice of a financial advisor. The appropriateness of a particular investment or strategy will depend on an investor’s individual circumstances and objectives.

An elegant, eloquent, and powerful start! Gonna be a great read.

It makes me consider the overwhelming power of AI taking over social networks.

And binge drinking, which likely hasn’t reached a pinnace yet.

At what point does binge become baseline, and powerful cannabinoids, ketamine, and (perhaps) other soon-to-be-available psychotropics dull the wider population even more than their smartphones already have?

Smartphone sports gambling probably gets there first.

When it goes Orwellian and is referred to as “Victory Bingeing”.

I got a small shudder when your autocorrect killed some humor when you simply copied and replied to part of my comments. That was not expected at all. Did you make a manual change?

“Pinnace” was intentional on my part, being part of the semantic meaning wordplay like Rusty and Shakespeare were having fun with in the article.

Spooky

I did make the change, thoughtlessly assuming that your autocorrect left intact a marine reference. I’m sorry - went right over my head. Hardly spooky, anything that goes on in there.

Rusty, do you think what you’re describing is a new field of study?

I don’t think so. It’s a multidisciplinary application, to be sure, but I think as we progress you’ll see that many of the underlying topics have pretty robust fields of scholarship to call upon.

May it bring scholars from around the world to a major university in Nashvegas.

Jim

In the beginning was the Word. And the Word was with God, and the Word was God.

Stepping down from the empyrean heights of the Gospel of John: humans have not done well when new media - new ways to tell the stories - have become widespread. Whether it was the printing press and the subsequent Reformation and Wars of Religion, to the newspaper and the revolutions in America and France, to broadcast media and the rise of both communism and fascism, to apparently social media today, it seems the less savory actors tend to harness the system first, only to unleash havoc that eventually settles into some sort of new, purportedly wiser order. That is, until the next form of media comes along.

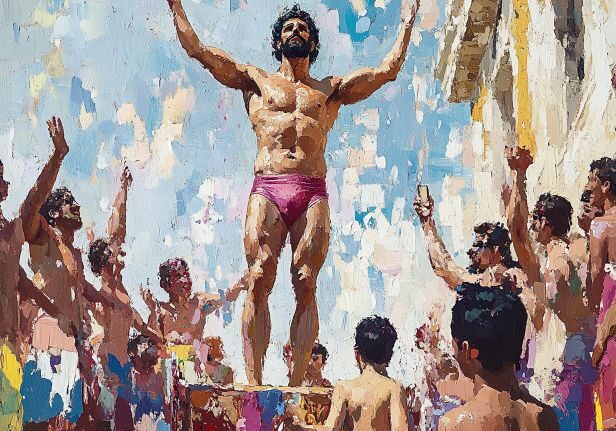

Reminded me of this:

Kurt Vonnegut on the Shapes of Stories

David Comberg 1.34K subscribers

2,050,888 views | Oct 30, 2010

Short lecture by Kurt Vonnegut on the ‘simple shapes of stories.’